Interest in the photographic print as a collector's object was formed in the world relatively recently. It was only in the mid-1970s that photographic prints began to be exhibited at the world's leading art auctions. Recently, the world market for art photography has been developing dynamically. Thus, the prices of individual works have already reached 6.5 million U.S. dollars. Collecting photographs and related activities is a relatively new field of study in Russia. Interest in acquiring photographic artworks as well as other types of photographic artifacts was a direct consequence of the crisis of the perception of photography as a visual document and was made possible by the dawn of legal commerce after the fall of the socialist system. Unlike the countries of Europe and America, where the art market in general and photography in particular was under less pressure from the state and developed gradually, the Russian art market was forced to overcome the lag that it had formed after the collapse of the USSR in relation to the countries of the West. This lag in the field of photography collecting is still quite significant. It is not only the result of skeptical attitude of the majority of population to the artistic potential of photography. At present, the vast mass of those interested still lacks a systematic understanding of the international norms regulating the processes of evaluation and subsequent acquisition of photographic works. This article offers a brief overview of the history of photography collecting and identifies a number of internationally established norms and rules, the knowledge and observance of which is mandatory not only for professional photography dealer and his customers, but also for authors who wish to succeed in the commercial realization of their works on the art market.

One of the first precedents in world history for the acquisition of a photographic artifact as a work of art is the purchase by Queen Victoria of Great Britain of O. Reylander's "Two Paths in Life" was one of the first photographic artifacts to be purchased by Queen Victoria of Great Britain. This work, created by Raylander in 1857 and depicting a scene from the Prodigal Son Parable, was one of the first attempts to imitate an easel painting through photography. This large work, made by means of combined printing from several separate negatives, thus claimed the right to be considered a work of art from the outset and thus implied, among other things, a correspondingly high material value of its value.

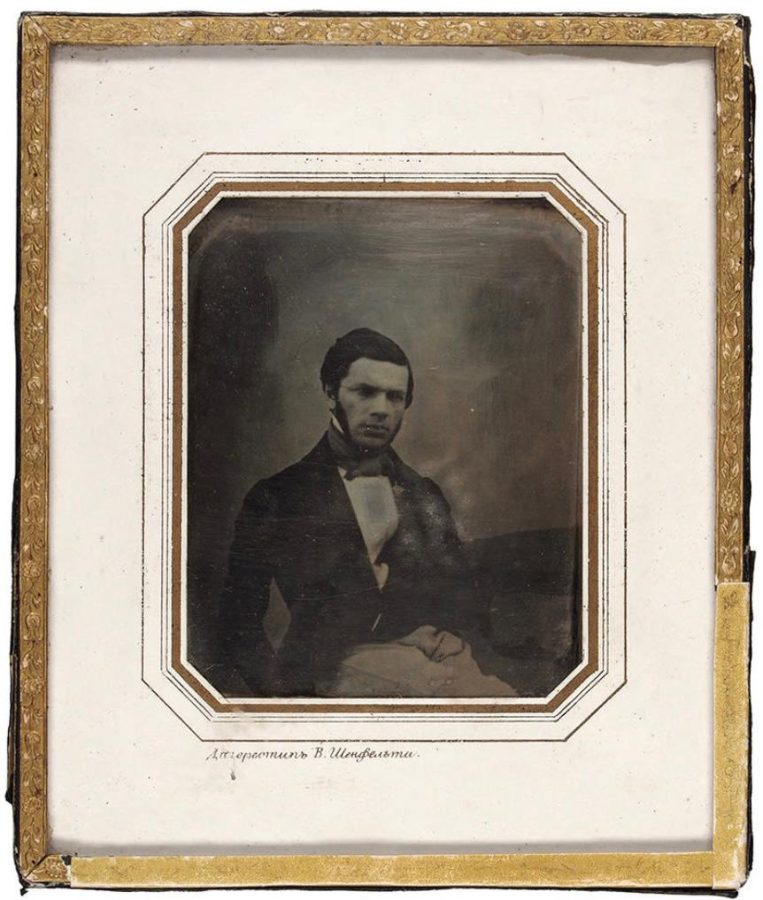

The first major collections of photographic artifacts were in one way or another related to the activities of the state. One such collection in the Russian Empire was the photographic and phototypical collection of the Imperial Public Library, in the compilation of which the famous publicist and art critic V. Stasov was actively involved. As in Great Britain, this collection had been systematically built up since the 1850s. The collection was divided into seven departments, including, respectively, the departments of views, folk types and portraits, architecture, painting, sculpture, prints and, finally, objects of artistic and industrial character. The main emphasis in the collection was placed on materials of interest to Russian history, ethnography and art. Despite the fact that the collection consisted primarily of artifacts originally focused on visual information, a number of them, such as works by V. Carrick, M. Nastyukov and T. Mitreiter, were considered in later eras as characteristic examples of Russian photographic art of those years.

A new stage of rapid interest in collecting photography came in the middle of the twentieth century, which coincided with the formation of key photographic collections in America. This interest was provoked by the boom of amateur photography after the invention of photographic film and first amateur cameras at the beginning of the 20th century, as well as by the development of independent trends in artistic photography after the crisis of Pictorial photography concept at the turn of the 1920s-1930s. The formation of new photographic collections necessitated academic research into the history of photography, among which The History of Photography, compiled in 1937 by Beaumont Newhall, a historian of photography and curator who was the direct organizer of the Photography Department at the MoMA, should be highlighted.

By the 1970s, photography was finally achieving the status of museum storage and collection worldwide. Thus, along with the creation of photographic collections at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the P. Getty Museum in Los Angeles, key European collections of photography were opened to the public at this time, among them the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, the Musee d'Orsay in Paris, the Museum Folkwang in Essen, the Museum Ludwig in Cologne. On the one hand, the opening of new photographic collections in Europe was related to the completion of the economic reconstruction of the region after World War II. Another important factor in the formation of photographic collections in the 1970s was the recognition of the creative merits of photographers working in the postwar period, both on the basis of the concept of the "decisive moment" and street photography, and the development of potentially new conceptual trends in photography under the influence of Pop Art and Hyperrealism concepts. Quite importantly, it was in the 1970s that color photography was recognized as a technology of museum value. For example, in 1976 John Jarkowski, the distinguished critic and historian of photography, organized an exhibition at the MoMA of works by William Eggleston, now recognized as one of the key masters of American art photography, who shot in color. The recognition of color photography meant the final establishment of all kinds of photographic artifacts as objects of cultural, and at the same time material, value to a wide range of collectors.

In order to gain the necessary insight into the specifics of the contemporary art photography market, it is necessary to identify a number of well-established concepts that define the rules of interaction of art photography market participants between themselves and with the complex of visual artifacts that interest them. We should begin, perhaps, by defining what is meant by the notion of the author of a photographic artifact. In the context of the creative photography market, the author is considered to be a single person or, in some cases, a creative team that necessarily combines the function of forming the creative idea of the future work and the function of control over the implementation of this idea in practice. The necessity to combine both functions in the activity is connected with features of the modern process of production of photographic artifacts. Thus, in the modern photographic industry the level of specialization is already extremely high and is steadily growing as a result of the constant improvement of photographic and computer technologies. For this reason, the production of a photographic artifact now involves not just one person, but a group of individuals consisting of narrow specialists in different fields.

However, not all of them can claim to own the copyright to the final product. Often, the specialists hired for their work serve as technical staff who, under the control of the actual author of the work, print the photographic artifact, process it and even shoot the subject directly. Such specialists do not make key decisions about the conformity of various technical parameters of the production process with the preliminary creative idea, but are guided in their activity by the requirements put forward by the author. In this case, the main project manager retains sole copyright to the final visual artifact, even if his creative will was implemented by others. One of the most striking examples of this kind of collaborative work from the practice of contemporary artistic photography is the creative team of American photographer Gregory Crewdson, which includes many specialists in photography, lighting equipment, computer image processing, etc. At the same time, the author of photographic works is still G. The author of the photographic works is still G. Crewdson, who does not even touch the camera in the process of shooting, but, nevertheless, he is the author of the idea and directs the activities of his entire team.

The degree of success of an author within the art photography market is directly influenced by his or her creative biography. Not only the author's education is important, but also the correspondence of his work to the logic of the development of world photography, knowledge of the heritage of famous maestros or creative schools of previous generations. For professional art critics or simply connoisseurs of photographic art, information about exhibitions where certain works of the photographer were exhibited is important. Collective exhibition projects are of the greatest interest, where the overall composition of the participants has an impact on each of them individually. In the field of solo exhibitions, attention is traditionally paid to major retrospectives, which are the hallmark of the biographies of only established authors. Exhibition catalogs, as well as other publications that allow one to analyze an artist's conceptual orientation, greatly enhance their creative status. An important factor in subsequent pricing is information on precedents of sales of the photographer's works at well-known art auctions, as well as references to well-known private or state collections where the respective works are currently stored. In the latter case, the dealers' attention is primarily attracted by references to major state museums of federal importance. One of the final, but certainly not insignificant, factors in the photographer's creative resume is his social status and the circle of communication associated with it, which, as well as other direct or indirect results of PR campaigns to enhance the artist's status, affects the degree of attractiveness of his work in the eyes of interested buyers.

Despite the fact that there is no single flawless system for evaluating the quality of photographic works, nor is there one in the field of art as a whole, we can identify several criteria that, in one way or another, fall within the field of view of art critics. The most difficult to define, but at the same time the most significant of these in the field of contemporary art, is the criterion of novelty, which implies the very generalized innovative essence of a work of art, which not only distinguishes the work from the previous artistic heritage, but also distinguishes a unique masterpiece from a copycat replica. The innovative qualities of the work in this sense can be manifested both in the technical execution of the artifacts and, much more importantly, in the use of a modern or even ahead of its time arsenal of artistic means of expression. The subsequent evaluation of photographic artifacts is undoubtedly influenced by the degree of cultural resonance they provoke among the relevant target audience.

Finally, of particular importance for the photography art market is the criterion of preservation of photographic works, especially in terms of capital investment. In this case it is not only the assessment of the immediate state of the artifact, but also the potential preservation of the photographic work over time and, therefore, the possibility of preservation and multiplication of the funds invested in the work. Even for the layman it is no secret that photographic prints are prone to so called fading under the influence of light radiation. The most obvious result of the corresponding exposure is the loss of image contrast. Destruction of the photographic layer under the action of light can be the consequence of both short-term intensive radiation and long-term exposure of the artifact to moderately illuminated environment. In order to prevent the fading of the image under the influence of light different methods are used, which most often can be summarized in three main actions. In order to maintain a high degree of preservation, it is recommended that photographic artefacts which do not require constant exposure be kept in vaults insulated from light. Works that are on display should be illuminated with special sources of light (cold - not hot) which have minimal effect on the artefact while maintaining the illumination necessary for comfortable viewing. As for the works produced nowadays, there are additional requirements for the selection of special materials that are resistant to the adverse effects of the environment. In the latter case, account is taken not only of the destructive effect of light rays on photographic artefacts, but also of the susceptibility of the photographic layer to change under the influence of various chemical compounds, such as, for example, sulfur gases contained in small doses in the air and also participating in the process of image degradation. As a result, currently manufactured photographic artifacts must not only be highly resistant to light, but also largely resistant to chemical attack. For the above reasons, special photographic papers with a barite layer are used in the field of black and white analog photography, designed for subsequent long-term collection storage. Because they contain a substance that is virtually inert and thus retains its original white hue for a long time, barite papers are widely used for the production of collectible prints oriented towards subsequent sales in the art market.

A similar situation of specific material selection takes place in the field of color photography, where image fading is particularly strong. In the modern lexicon of the photography collector the term primordial color is firmly established, applied to color photographic prints that have changed their original coloring over time under the influence of light and chemical reactions. It should be noted that it was the destruction of one or more components responsible for a particular color in polychrome photography that was the reason why museums and private collections have long refused to acquire and store works of color photography in their collections. Recall that color photographic prints did not become collector's value until the 1970s, and this was largely due to the fact that it was at that time that more persistent processes, such as sibachrome, began to be used to print works of photographic art. Appropriate printing techniques requiring the use of highly toxic chemicals and special conditions for the disposal of production waste made it possible to produce prints that remained virtually unchanged for decades, and thus could become collector's items and large financial investments. For the same reasons color photographs have recently been produced using printers that use special pigmented inks, which guarantee the prints' high resistance to subsequent destruction.

In order to strengthen the resistance of prints to alien chemistry as well as to protect them from excessive mechanical impact, plasticization technology is actively used in the production of modern photographic art works. This process implies coating a photographic print with a layer of transparent acrylic which, after hardening, not only protects the work from accidental damage, but also hermetically insulates its surface. With the latter, plasticizing technology, which is highly valued in the art market, is vastly superior to traditional glass, which somehow maintains a gap between the print and the protective surface, into which air continues to permeate. It is also worth noting that plastification technology, originally invented to ensure the preservation of a photographic print, is now seen not only as a technical, but also as an artistic property of works of contemporary photographic art, with the result that its application now goes beyond issues of conservation, and the corresponding works are successfully sold at leading auctions and are highly valued by the international museum community.

The process of rolling a photographic print onto so called ‘dibond’, which serves as the basis for the artifact, is also one of the technologies that has now transcended applied tasks and has become a distinctive feature of modern art photography. Dibond, which surpasses cheaper foam board in strength and resistance to bending, is distinguished primarily by a special thin metal coating, polished to a mirror finish and thus makes it possible to level out the penetration of the surface under the actual photographic print. The use of dibond, which is a more economical and convenient material than aluminum sheet, was one of the factors that influenced the change in the formats of contemporary photographic art towards their increase, which affected the composition of the works on the art market.

The key concepts for the photographic art market that define the conditions of its functioning are also vintage, late print and contemporary print. These definitions are necessary to distinguish the categories of prints in the sphere of art market functioning, because it is possible to create almost identical prints or even superior in technical characteristics to the original work a considerable period of time after the shooting or even after the death of the author. In any case, it would produce works that do not correspond to their socio-cultural context.

A vintage print is a visual artifact made directly by the author or under his direct control a short period of time after the photograph was taken. Insignificant time in this case refers to a period of time during which no radical changes in the technology of the photographic process or in the cultural environment have taken place. Thus, a photographic artifact made by the author using more modern technology, or made in accordance with new creative concepts under the influence of changes in the ideological environment, does not correspond to the original technological or cultural environment, so it cannot be included in the category of vintage. It should also be noted that in the current situation of rapid acceleration of technological progress, dynamic changes in public opinion and an abundance of high-profile events, the time period stated in the definition of vintage has significantly shortened and continues to shorten, requiring from the author a greater degree of promptness in the production of vintage visual artifacts. It should also be noted that the concept of vintage in the context of the photographic market is not synonymous with "old," rarity photography, as is often mistakenly claimed. From the point of view of the creative photography market, vintages are of the greatest historical and commercial interest. It is vintage works that make it possible to assess the degree of insight of their authors' thinking, to convey with the greatest degree of authenticity the specificity of the author's perception of the surrounding world, as well as to evaluate the magnitude of a particular author's or artifact's contribution to the visual culture of today.

The next category of visual artifacts includes late prints. They are works made by or with the direct participation of the author, but a considerable amount of time has passed since the photograph was taken. Late print artifacts are still of interest within the creative photography market, but they are no longer perceived by critics and photography connoisseurs as works of primary value. These prints in any case bear the stamp of later technological and creative achievements of later eras, and thus are not as authentic as the vintages. For the same reason, the value of a photographic print belonging to the category of late prints is significantly lower than a vintage print. This situation is particularly characteristic of Soviet photography of the war and postwar years, where for various reasons a significant proportion of vintages were not made or have not survived.

The final category of visual artifacts is modern prints, which include works made a considerable period after the photograph was taken without the participation of the author, most often by the heirs or other rightholders of the archive. This category of photographic works is of almost no interest in terms of serious collector's investments, since the lack of authorial control over their production leads to an irreversible loss of authenticity of these works from the perspective of connoisseurs and art historians. Accordingly, on the photographic market modern prints are usually priced substantially lower than later prints and even more so vintage prints. Nevertheless, it is precisely because of their relatively low value that contemporary prints, often made using more modern photographic technologies, are used for interior design purposes, where the main purpose of using the work is its visual, rather than its historical or commercial component.

Another important parameter that establishes the conventional rules for the functioning of the creative photography market is the category of circulation. The ability to replicate images, which has been perceived as a key technological virtue of photography since the first two-step process of calotyping invented by Fox Talbot, has always been seen as a key drawback from the perspective of the artwork market, since this market has always been built on the principle of exclusivity of the product offered. In order to bring the mechanical process of photography in line with this age-old tradition, as well as to control pricing, the need arose to assign serial numbers to photographic artifacts, indicating the total circulation of identical works. At present, it has become an international norm for photographic works intended for a serious market of creative photography to indicate the sequential number of a given print and the total number of all identical copies of that work. The relevant information directly affects the value of this or that work. Reducing the print run naturally increases the cost of the work. In some cases, the print run may be limited to a single work, the uniqueness of which the author usually seeks to confirm either by providing the buyer with the original negative or file, or by publicly destroying the source material. Increasing the print run, on the other hand, is usually used when the author decides to sell a larger number of prints at a lower cost, but in the end to achieve a commensurate profit. This situation is more typical for underdeveloped regional art markets, where the buyer is not morally or financially ready for a higher capital investment. The serial number of the print also plays an important role. The value of the artifact increases as the number of works potentially available for future purchase decreases. It should be noted that it is often the practice of authors to make only a few prints of the original print run in order to make an initial profit and then spend some of it to make the rest of the declared identical copies.

The conditionality of the limitations imposed on an array of photographic artifacts by market requirements has always led to the temptation to falsify information as to whether a particular artifact belongs to a particular qualitative or quantitative category of prints. In this case, even the most accurate examination can only partially authenticate the information in question. While there are a number of technical and analytical ways to distinguish vintage from late or modern prints, determining the circulation of works is largely difficult and still largely depends on the good faith of the author or his representatives. At the same time, cases of uncovering false information about a visual artifact by a market participant usually led to severe consequences for the latter, which may lead not only to the termination of relations with buyers, but also to the prosecution of the detected fraudster.

In today's environment of great complexity in every field of human activity and the resulting deepening of labor specialization, the role of the gallery as an intermediary between the field of art and the field of commerce continues to grow. To ensure competent compliance with the rules of the art market, the author's own knowledge, means and connections are no longer sufficient in most cases. Some of the services a gallery provides to contemporary artists include organizing and conducting timely displays of works of art for the target audience, searching for interested buyers, and evaluating the value of artifacts for sale. The issues of organizing reliable security and insurance for the exhibits also play an important role. There are also cases where galleries provide the author with access to expensive or exclusive equipment needed for photography or printing. All of these services, which are important for the successful sale of works of art, require additional expenses and must be competently and legally formalized in the terms of the contract concluded between the author and the gallery. Taking into account that there are a lot of requirements and conventions of the art market, existence of specialized galleries must be considered as a sign of market development in one country or another and as a factor influencing the possible amount of authors working on the art market. Because a gallery has a fixed budget it can only work with a limited number of authors. Taking into account the fact that galleries usually specialize on work with local national authors who can be approached by customers from different regions of the world, the absence or lack of viable galleries leads to serious restrictions on the introduction of national art to the global international arena. In this regard, the level of development of the art market in photography, as well as art in general, is one of the indicators of a country's well-being, making the support of national art in one way or another one of the most important areas of state policy.

The above-mentioned specifics and rules of the photography art market give us a cursory idea of the degree of difficulty of serious photography collecting. However, both the difficulties associated with collecting photography and the intellectual effort and material resources required for these purposes are generously offset by the growing popularity of this kind of activity, due both to the availability of a wide range of new unexplored topics and materials of Russian origin and to the rapid development of contemporary photographic art in the world at large.

Artem Loginov