Like any highly developed sphere of activity, photographic art constantly shows signs of an unsolvable dilemma, which is the difference in the level of professional and cultural training between the field specialists who create artistic works and the average viewers who have only a superficial idea of the degree of development of photographic practice. What, from the point of view of photographers, is a creative achievement and a necessary aesthetic innovation, causes misunderstanding and legitimate surprise of untrained public and clients, which, in turn, often grows into denial of their own unprofessionalism and unflattering criticism.

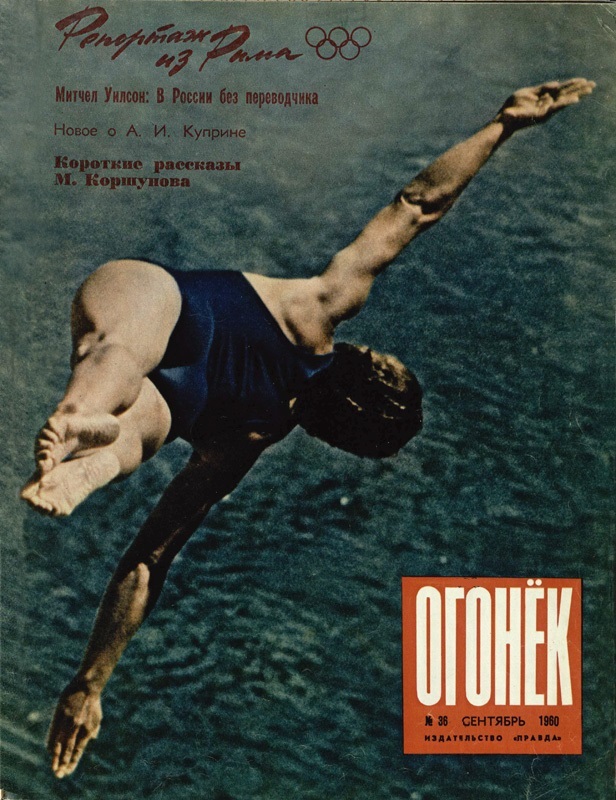

As an illustrative example, the famous Soviet photographer Lev Borodulin once told a story. Borodulin spent his entire life specializing in sports photography, an area in which he became an acknowledged expert, but he was also a respected connoisseur and collector of photographic works. During his regular trips to the USSR from Israel, where he had decided to emigrate, he often stopped by to see my father, with whom he shared his experiences and vivid memories from his own life. One such story was about the famous shot Borodulin took at the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome. During the diving competition, Borodulin climbed to the top of the diving tower from which the jumps were performed to film the athletes who were jumping from a lower tier. Thus, the shot was taken from top to bottom, almost perpendicular to the pool, with an active angle that allowed for a non-standard composition. From Borodulin's point of view, this was the way to shoot sports events, i.e., to achieve unusual artistic solutions even in the demonstration of familiar events.

We must pay tribute to the high level of preparation of Borodulin's colleagues from "Ogonyok" magazine, who perceived and appreciated the picture provided to them in the same way, and therefore put it on the cover. After all, the picture showed the dynamics of sport, the athlete's free flight at the decisive moment of his jump, that is, in every way it could become a symbol of the Olympics. However, the frame was interpreted quite differently by Mikhail Suslov, the then Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee and one of the main party ideologists. Seeing the cover of "Ogonyok" with Borodulin's photo, Suslov was unpleasantly surprised by its composition and at one of the sessions he angrily referred to the frame as nothing less than a "flying ass". Suslov, who had no understanding of photographic art, wanted to see quite standard shots, "decent" in terms of his own conservative understanding of artistic creativity. Naturally after such an appraisal on the highest level, Borodulin was immediately recalled from the Olympics, and in the following years he was repeatedly criticized. Eventually the photographer decided to emigrate to Israel.

It should also be noted that the situation that Borodulin faced in his work was not out of the ordinary for Soviet photography. Long before this event, a similar case occurred with respect to the treatment of the master of Soviet photography, Alexander Rodchenko. His famous 1932 work "Pioneer Trumpeter", for its active perspective, though in this case from the bottom up, was criticized as an example of formalism in Soviet photography. It is also indicative that even after a considerable period of time and changes in the political leadership of the country, the problem of the gap between author and viewer did not disappear, and the vigilant attention of Soviet ideologists to photography as one of the main instruments of propaganda was not diminished even during the Khrushchev "Thaw".

Artem Loginov, for "History of One Photo"